Sexual abuse institutional cover-up survivor Javier Alcántara breaks a crack, and the light gets in.

“The essence of journalism is dramatic. The authentic journalist hides his own and reveals that of others; he gathers dispersed vibrations within himself and transmits them; like an actor, he disappears beneath the reality he conveys to us.”

Rafael Barrett

Our Exclusive Interview with the Victim Javier Alcántara

In an ecclesial Aragón (county in Spain) marked by silences, inexplicable promotions, and links that were never investigated, the voice of Javier Alcántara bursts forth with force in a territory where cover-up ceased to be an anomaly and became a system. His testimony dismantles the official narrative and exposes how, for years, a structure of clerical impunity has been sustained—one that protects the same people over and over again.

The arrival of Pedro Aguado as bishop of Huesca-Jaca is no mystery: it is a signal. From Zaragoza city to the Pyrenean valleys of Aragon, clerical impunity has become a structure of power. Javier Alcántara’s voice opens yet another real crack in that wall.

Enjoy your reading.

Jacques Pintor

The Rise of Pedro Aguado in Huesca-Jaca and the Network of Sex and Cover-ups in Aragón

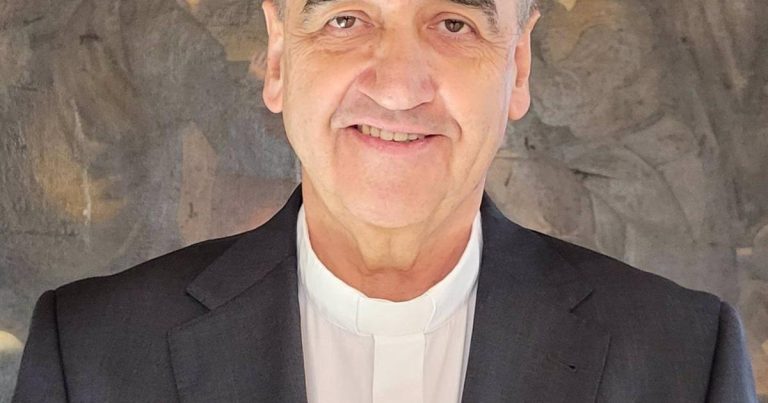

The arrival of Pedro Aguado in the diocese of Huesca-Jaca is neither an innocent nor a casual move. It is especially striking when one observes the ecclesial map of Aragón, where the dioceses of Zaragoza, Teruel-Albarracín and Huesca-Jaca remain, as our investigation shows, under the influence of Cardinal Juan José Omella. Only Tarazona, despite belonging to the ecclesiastical province of Zaragoza, escapes this scheme; its bishop is an extremely discreet figure, practically absent from public debate, alien to the media exposure that accompanies his neighboring bishops.

In Aragón, cases accumulate that trace a pattern of clerical impunity sustained by a structure of silences. In Zaragoza, priests implicated in sexting continue in ministry; one of them, reported for sending indecent images to a layman, went to trial and avoided consequences through a forgiveness agreement ratified in court. He continues to hear confessions at the Basilica-Cathedral of Our Lady of the Pillar (El Pila). There is also the case of Reverend Ignacio Ruiz, head of heritage at La Seo Cathedral (yes, Zaragoza boasts of two Catholic cathedrals), internally reported by other canons for improper conduct toward young men. Far from opening a process, he was promoted to canon. The complaint filed with the Office for the Prevention of Abuse of Aragón —centralized under the current seminary rector, Javier Pérez Mas— also produced no results.

SEE ALSO: PHOTO OF A ZARAGOZA PRIEST’S PHALLUS SENT BY WHATSAPP. THE ARCHBISHOP DOES NOTHING (following soon)

In this context, the inevitable question emerges: what sustains this network? Who has whom in check? Cases such as that of priest Gonzalo Ruipérez, with two children from two different women whose offspring were admitted to the seminary in Madrid and ordained under different identities, open questions about what relationships, pressures or tacit pacts operate not only in the diocese of Zaragoza or its neighboring Aragonese dioceses, but in Spain as a whole.

SEE ALSO: CARDINAL ARCHBISHOP OF MADRID HID DENOUNCEMENTS AGAINST HIS PRIEST LOVER OF VULNERABLE WOMEN, FATHER OF TWO CHILDREN (following soon).

The figure of the person responsible for the Defense of the Bond in the Diocese of Zaragoza and her historical relationship with priest Gonzalo Ruipérez (father of two children by two different women and lover for nine years of a parish worker, while giving religious talks at an Opus Dei priests’ center) feeds hypotheses about why certain behaviors, structures and figures remain untouchable. This omertà could be explained as a balance of mutual compromises —for example, the protection of a priest involved with drugs in a diocesan apartment and sex in homosexual swing clubs: the Reverend Enrique Ester. It would also explain the survival of pressure groups within the Zaragoza clergy that led to shelving the report on the known as “Trama Maña scandal” (Clerical Plot of power in Aragon), which passed through the hands of the now canon and former vice-rector of the seminary, diocesan priest, Opus Dei member and identified as head of the gay lobby in Zaragoza, the Reverend José Antonio Calvo.

Returning to this soap-opera look-alike (SOE) of the Diocese of Huesca-Jaca serves to close the circle. There, the bishop prior to Pedro Aguado Cuesta, Julián Ruiz Martorell, ordained a young man whose prior sexual life —documented by the second seminary he attended, the military seminary in Madrid— included practices in gay swap venues and alcohol consumption before reaching adulthood. Three years later, Ruiz-Martorell promoted him to public office. The question arises again: how many similar episodes lie silently in the archives of these dioceses?

Against this backdrop —a episcopal structure with systemic failures, deliberate silences and a documented history of cover-ups— the figure of Pedro Aguado now appears. His arrival in Huesca-Jaca is a move that deserves to be read in the light of all the above. And it is within this framework that this exclusive interview conducted by our colleague Jordi Picazo with the Mexican Javier Alcántara by telephone conference takes on particular relevance. Alcántara is one of the victims whose case opens deep cracks in the official narrative.

Javier Alcántara Speaks

JAVIER ALCÁNTARA (JA) – In Pedro Aguado’s case, friends at El País helped publish a new article showing that [Aguado] covered up for nine years a priest —my aggressor. I did not know that detail until recently, when everything was already reported and when Pedro Aguado [now appointed bishop in Spain] decided to keep silent. That opens an enormous panorama for media investigation, though not so much for criminal or civil justice, because—as my own lawyer told me—judicially the case is almost exhausted.

Right now, my main tool is public exposure. I already have an investigation file at the prosecutor’s office. I have given my testimony in the media: I appeared on the air with Azucena Uresti, now in El País and in Los Ángeles Press. From Spain I was also contacted by RTVE. The recent case of Father Baltazar’s testimony is key. I have audios where he says that his bishop already ordered him to keep quiet. I uploaded only a fragment because of how delicate the matter is, but it is clear: he was silenced, received a call “from above” and was warned he could even lose his incardination in the diocese. I, on the other hand, am not backing down. I will not step aside. I want to get to the bottom of this, not only for myself: there are more victims.

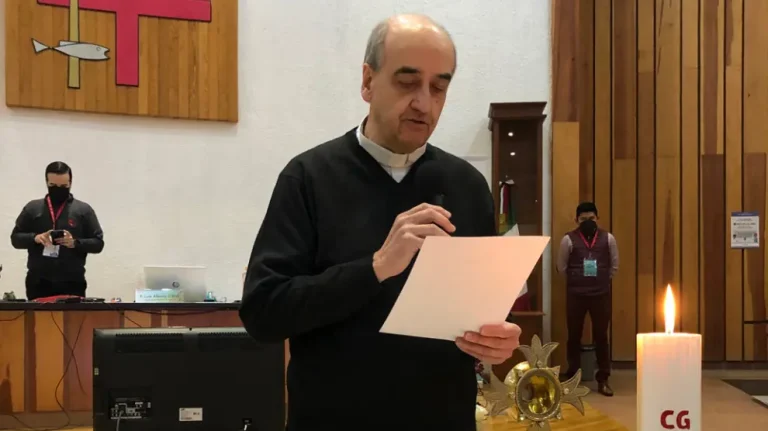

My aggressor was Father Miguel Flores. I want to understand how his case, José Antonio Satué [bishop in Aragon, Spain and promoter of homosexuals into the clergy] and Pedro Aguado (now bishop in Aragon as well as Satué until recently and Julián Ruiz Martorell) all connect within the same network. It is a matter of piecing together the puzzle: Pedro Aguado was a consultant to a dicastery in Rome, was involved in ecclesiastical politics, had power and knew what was happening. I posted a tweet asking how it was possible that Pedro Aguado was judge and party in all this. And when Pedro’s appointment as bishop was announced (March 29, 2025), [Pope] Francis was practically already dying; he passed away 23 days later, on April 21. By then, Francis was no longer really aware; or he signed appointments almost routinely. Once they are bishops, in practice they become untouchable.

JORDI PICAZO (JP) – We would need to thoroughly review the relationship between José Antonio Satué—eight years at the Dicastery for the Clergy—and Pedro Aguado, both already reported to civil authorities. Being bishops seems to give them an aura of immunity, but that is not the case. This is a culture of criminal impunity.

JA – And it is not only my case. Pedro Aguado led the Order [of the Piarist Fathers] for 15 years. There are other documented cases. In Colombia, for example, another journalist has identified at least three validated cases of Spanish Piarist priests who caused great harm there. There were more, but these three are documented. And they were silenced: when they were about to give testimony, they disappeared.

SEE ALSO, NEW BOOK: “SATUÉ, AN INVESTIGATION REPORT” (following soon).

JP – Did Father José Miguel die in Spain, or not?

JA – No, he died in Mexico. And there is another inconsistency there. Miguel spent a year in Spain, around 2012–2013. Then they sent him back to Mexico and gave him obedience to go to Ecuador, to Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas or de los Colorados —it is the same area. From then on I had almost no contact with him until I fell into drugs. In 2017 I was institutionalized, began my recovery and decided to report him. I did it late, yes; I myself think I should have reported earlier, but that is where the Church’s manipulation comes in.

Pedro Aguado told me: “Don’t worry, if the sentence comes out in your favor, I myself will report him civilly; that is what is proper.” Back then I did not know the content of the Pope’s motu proprio “Vos estis lux mundi” nor the scope of that regulation. I trusted his word. In 2020 the Vatican sentence against Father Miguel is issued: he is removed from the clerical state and expelled from the Order. Pedro claims that since 2018, when he became aware of the facts, he removed him from Ecuador and sent him to a monastery in Peralta de la Sal, in Spain. That is where the contradictions begin: he was never in Peralta de la Sal, but the whole time in Mexico City. They removed him from Ecuador, yes, but brought him to Mexico and kept him close to children and young people.

JP – How do you know he was never in Spain?

JA – Because I have photos and because Pedro [Aguado] gave himself away. When I am given my life plan, Pedro asks me: “Would you be willing to confront Father Miguel right now and repeat to his face what you told me?” I answered yes. Then he slips and tells me: “It’s just that he’s at the provincial house, here in Mexico.” I reply: “Wasn’t he in Peralta de la Sal, in contemplative life?” He tries to correct himself by saying that he has him “isolated,” in “contemplative life.”

In addition, a Spanish Piarist friend, who has known me since childhood, tells me when I am in Veracruz —where they sent me to study and work— : “I saw your godfather.” He knew nothing about the abuse. He tells me: “He’s in Tlaxcala.” That is when I begin to investigate: I discover that Miguel has a Facebook account, photos with children and young people, celebrating Mass, in a church, at the Colegio Morelos of the Piarists. I ask Pedro again: “Wasn’t he in Peralta, isolated?” I have all those emails.

All this connects with the relevance of the dioceses of Huesca and Jaca. The bishop before Pedro —not Vicente, the one before, a thin man with glasses [Ruiz Martorell]— also has accusations related to ordaining unfit candidates. It is a pattern: they cover for each other, bishops and priests.

JP – Even the cardinal prefect of the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith has been implicated in cover-ups in other cases.

JA – I feel that public exposure weighs more for me than the judicial route. The Public Ministry itself told me: “The order from above has arrived, money was released, and your file was shelved.” I appeared on television and even so it was shelved. I fight to have the case taken up by the Office of the Attorney General. It is an uphill battle: even with Human Rights I am fighting; they do not want to act, despite reports documenting how my life was destroyed, my psychological illnesses, the deep harm.

They have not even wanted to show me the complete sentence of the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith. My aggressor continued to celebrate Masses with young people. They say it was only one Mass: that is not true. I have photos of several dates, in Piarist institutions, at the front, as if nothing had happened. In Mexico the crime of cover-up exists, but there is no one to apply it. I am fighting with Father Baltazar’s testimony to prove Pedro Aguado’s cover-up. My mother was the one who first spoke with Pedro, because I was hospitalized in a rehabilitation center in 2018. That is when we presented the canonical complaint. Pedro summoned my mother, spoke with her, and assured her that he would do everything “properly” according to his canons —I now understand he was referring to the motu proprio Vos estis lux mundi— and that, if Miguel were found guilty, he himself would hand him over to civil authorities.

Father Miguel [Flores] was supposedly sent to Spain after leaving Ecuador in 2018. In theory, he had precautionary measures from 2018 until 2020, when he “died.” But what we do know is that he was never in Peralta de la Sal, unless they show me the passport with the entry stamp to Spain and the exit stamp in 2020.

In recent months, a Colombian journalist, Miguel Estupiñán, contacted me. He told me he has an investigation into Spanish Piarists who abused minors in Spain and Colombia, from the 1960s to the 2000s. There are three Spanish priests, with dozens of victims. What relevance does Pedro Aguado have there? That those cases are reported to the Piarists in Catalonia, Spain and the Piarists do nothing. The provincial in Barcelona, named Jordi, receives a complaint from a young man in 2015. When justice is about to formally take his statement, the case disappears.

JP – Very similar to what happened in Zaragoza, where a priest who sent indecent messages asked for forgiveness just before trial and continues hearing confessions in the cathedral.

JA – The news reaches Pedro Aguado, then general of the Piarists. He attends to the complainant by phone, promises attention, and then disappears: he never responds again.

JP – In other words, this young man first seeks out the provincial and gets no response. Then he seeks out Pedro Aguado as superior general; Pedro listens to him by phone, tells him everything will be fine, and then cuts off all communication.

JA – Exactly. That is why, in Mexico and Colombia, we want to show that Pedro Aguado’s way of acting is always the same. It is not an isolated case in Mexico. There is also a Spanish Piarist missionary in Senegal, accused of abusing many children and young people from the 1990s until 2005. That case was also kept covered up. Pedro put out fires, but in the end everything remained under cover-up.

He never filed complaints with civil justice against any of these priests, despite the obligation established by Church regulations. Everything stayed inside, even betraying Pope Francis’ motu proprio “Vos estis lux mundi”, which is very clear: if the Vatican sentence declares a priest guilty, there is a moral and civil obligation to report him to the police where the acts occurred.

I communicated all this to Pedro. He “separates” Father Miguel, shows me the sentence on October 8, 2020, and I remain calm because he tells me: “Father Miguel is already removed, he is no longer near anyone. I will ensure that he is not near people, does not celebrate Masses, does not have contact with young people. He is in Mexico, at his mother’s house; I will try to make sure he leads a civil life, but always kept away.”

Later I am told that he supposedly dies. I go on Facebook and see that the provincial father, Fernando Hernández —who is still provincial today— attends the funeral Mass. I cannot affirm whether he is alive or dead, but there is a serious inconsistency that I will detail later. At the Piarist university of Veracruz they publish an obituary that says “Father José Miguel Flores Martínez.” I think: they could have put only “Miguel Flores, former Piarist” or “Mr. Miguel Flores.” But they present him as a Piarist priest. There they are recognizing that he remained a priest until the end. They almost canonize him: that “he was an excellent priest”, etc.

I ask Pedro again what is going on. He replies that it was “a mistake,” that he already spoke with Fernando, that they will offer me apologies. Always treating me as if I were foolish.

Over time, I see that nothing changes: Fernando remains provincial, Miguel appeared in contexts of total impunity. I decide to cut all communication with Pedro, stop answering his emails and file a criminal complaint.

I report Miguel Flores for aggravated rape, and I also report Pedro Aguado, Fernando Hernández and José Luis Sánchez, the bursar who paid for my studies at the Piarist university. I file the complaint with the Mexico City Prosecutor’s Office. They accept the file, but only as aggravated rape against Miguel, not for institutional cover-up, which is what interested me most.

I am assigned a public defender. He tells me that the Prosecutor’s Office does not want to accept the cover-up charge, that it was already difficult just to open the investigation. In the end, they only indict the aggravated rape against Miguel, even though I provided the names of Pedro, Fernando and the bursar. There are people within the prosecutor’s office who are aligned with the Church. My lawyer warns me: “If they manage to prove that Miguel is dead, everything ends there.”

Two or three months later I return to ask: “How is my case going?” The answer is: “There is nothing. We are still waiting for a copy of Father Miguel’s death certificate.” That certificate never arrives. If it does not arrive, for me it means he is alive, and an arrest warrant should be issued.

From the beginning I sought out activist Ana Luz Salazar. She told me she would support me. I start appearing in the media: first in Los Ángeles Press, anonymously; then with Azucena Uresti, also anonymously, by phone. When we see that the file is stalled, I decide to show my face, with full name, and also publicly denounce the prosecutor’s office for its inaction. I appear on her program, and the case begins to gain strength. Then I appear in other newspapers and, finally, I contact El País’ abuse commission. I send them all the documents and they publish the report.

Several times the Piarists’ lawyers have tried to coerce me. They present themselves as repentant, very interested in helping me. They approach my lawyer and literally say: “How much does the boy want for all this to stop?” I respond that, if we talk about comprehensive reparation, it must have several points: it must be based on medical and psychological reports, that experts set the amount, and that there also be a public apology. They have time for conferences, statements and speeches, but they never had time to send me an apology, neither from Fernando, nor from Pedro, nor from anyone. On the contrary, they insist that “they did everything right.”

I ask my lawyer to include a clear clause: I will not renounce my civil or criminal rights. Recently I return to the prosecutor’s office… and my file had “disappeared.” I confront the prosecutor: it had been stalled for six months. The crime of cover-up prescribes in one year. We had already consumed half of the term. I demand to speak with the Attorney General. Her advisor receives me. But my lawyer reminds me that there are members of the clergy moving within the prosecutor’s office to keep the file frozen. They tell you: “There is no progress,” and that’s it.

I have the smoking gun: Father Baltazar Sánchez’s testimony. With his declaration and with my 2018 testimony, the cover-up is clear. Pedro Aguado does not come from just anywhere: he comes from Rome, was responsible for the Dicastery for Education and superior general of the Piarists. He was always in Pope Francis’ ear. Father Baltazar has the right to refuse to testify, but he himself made it public that he had informed Pedro of two cases before mine. He allowed his name to appear in El País. The problem is that his bishop —also accused of cover-up— called him to order him to keep quiet. Since Baltazar is a Piarist and is incardinated in a diocese, his stability depends on that structure. He first wanted to speak; now he withdraws because they pulled his ears.

That is also a crime: continuing to cover up. Even if he retracts, there is no going back: he already spoke publicly. It is information in the public domain. And with that, we will continue. I do not intend to stop.

READ PART 2 OF THIS INTERVIEW: Breaking News | Javier Alcántara Reveals the Firewall that Protected the Bishop of Huesca-Jaca, Pedro Aguado: The Trap Closes.

YOU MAY ALSO READ:

– Environment of Spanish Bishop Pedro Aguado Tried to Silence the Victim after Reporting Piarist Cover-up

This article was first published on November 25, 2025.

By Jacques Pintor.

All rights reserved, @jacquespintor 2026.

For contact, you may want to write to us at jacquespintor@gmail.com.

Find us on Twitter @jacquesplease.